Many thanks to Thomas Vander Wal for the many conversations that inspired this post.

The average life expectancy of a human being in the 21st century is about 67 years. Do you know what the average life expectancy for a company is?

Surprisingly short, it turns out. In a recent talk, John Hagel pointed out that the average life expectancy of a company in the S&P 500 has dropped precipitously, from 75 years (in 1937) to 15 years in a more recent study. Why is the life expectancy of a company so low? And why is it dropping?

I believe that many of these companies are collapsing under their own weight. As companies grow they invariably increase in complexity, and as things get more complex they become more difficult to control.

The statistics back up this assumption. A recent analysis in the CYBAEA Journal looked at profit-per-employee at 475 of the S&P 500, and the results were astounding: As you triple the number of employees, their productivity drops by half (Chart here).

This “3/2 law” of employee productivity, along with the death rate for large companies, is pretty scary stuff. Surely we can do better?

I believe we can. The secret, I think, lies in understanding the nature of large, complex systems, and letting go of some of our traditional notions of how companies function.

THE COMPANY AS A MACHINE

Historically, we have thought of companies as machines, and we have designed them like we design machines. A machine typically has the following characteristics:

1. It’s designed to be controlled by a driver or operator.

2. It needs to be maintained, and when it breaks down, you fix it.

3. A machine pretty much works in the same way for the life of the machine. Eventually, things change, or the machine wears out, and you need to build or buy a new machine.

A car is a perfect example of machine design. It’s controlled by a driver. Mechanics perform routine maintenance and fix it when it breaks down. Eventually the car wears out, or your needs change, so you sell the car and buy a new one.

And we tend to design companies the way we design machines: We need the company to perform a certain function, so we design and build it to perform that function. Over time, things change. The company grows beyond a certain point. New systems are needed. Customers want different products and services, so we need to redesign and rebuild the machine, or buy a new one, to serve the new functions.

This kind of rebuilding goes by many names, including re-organization, reengineering, right-sizing, flattening and so on. The problem with this kind of thinking is that the nature of a machine is to remain static, while the nature of a company is to grow. This conflict causes all kinds of problems because you have to redesign and rebuild the company while you also need to operate it – an idea dramatized in an EDS commercial from a few years ago: Building an airplane in flight.

THE COMPANY AS AN ORGANISM

It’s time to think about what companies really are, and to design with that in mind. Companies are not so much machines as complex, dynamic, growing systems. As they get larger, acquiring smaller companies, entering into joint ventures and partnerships, and expanding overseas, they become “systems of systems” that rival nation-states in scale and reach.

So what happens if we rethink the modern company, if we stop thinking of it as a machine and start thinking of it as a complex, growing system? What happens if we think of it less like a machine and more like an organism? Or even better, what if we compared the company with other large, complex human systems, like, for example, the city?

Cities are large, complex, systems, but we don’t really try to control them. In Stephen B. Johnson's book Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software

Cities have no central planning commissions that solve the problem of purchasing and distributing supplies… How do these cities avoid devastating swings between shortage and glut, year after year, decade after decade?No, we don’t try to control cities, but we can manage them well. And if we start to look at companies as complex systems instead of machines, we can start to design and manage them for productivity instead of continuously hovering on the edge of collapse.

Cities aren't just complex and difficult to control. They are also more productive than their corporate counterparts. In fact, the rules governing city productivity stand in stark contrast to the ominous “3/2 rule” that applies to companies. As companies add people, productivity shrinks. But as cities add people, productivity actually grows.

A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia found that as the working population in a given area doubles, productivity (measured in this case by the rate of invention) goes up by 20%. This finding is borne out by study after study. If you’re interested in going deeper, take a look at this recent New York Times article: A Physicist Solves the City.

Okay, you say, but cities are fundamentally different than companies. Just because this works for cities doesn’t mean that it will work for companies. Right?

THE LONG-LIVED COMPANY

Actually there’s some interesting data there too. Back in the early 1980’s, right after the revolution in Iran, Shell Oil was concerned about the future of the oil industry. What might Shell look like after oil, they wondered? So they commissioned a study with some very interesting parameters:

1. First, they looked only at large companies with relative dominance in their industries, companies similar to Shell in that regard.

2. Second, they looked only at companies with very long lifespans – 100 years or more.

3. Third, they looked at companies who had made a major shift from one industry or product category to another.

In other words, they looked at the immortals: the companies that didn't die.

The study was never published, but the findings were detailed in a book: The Living Company

Interestingly, these companies had a lot in common with large cities:

Ecosystems: Long-lived companies were decentralized. They tolerated “eccentric activities at the margins.” They were very active in partnerships and joint ventures. The boundaries of the company were less clearly delineated, and local groups had more autonomy over their decisions, than you would expect in the typical global corporation.

Strong identity: Although the organization was loosely controlled, long-lived companies were connected by a strong, shared culture. Everyone in the company understood the company’s values. These companies tended to promote from within in order to keep that culture strong. Cities also share this common identity: think of the difference between a New Yorker and a Los Angelino, or a Parisian, for example. At the Dachis Group we like to call this common culture hivemind.

Active listening: Long-lived companies had their eyes and ears focused on the world around them and were constantly seeking opportunities. Because of their decentralized nature and strong shared culture, it was easier for them to spot opportunities in the changing world and act, proactively and decisively, to capitalize on them. At Dachis we sometimes call this dynamic signal (watching and listening) and metafilter (information leading to decisive action).

DESIGN BY DIVISION

Historically we have designed companies like machines – by division. We construct the org chart to divide the big chunks of work and separate them from each other: Finance, Sales, Operations. We design the work flows that process inputs into outputs: raw materials into products, prospects into customers, complaints into resolutions.

As we design this kind of company – the divided company – we need to separate functions, which means people may not always have a sense of the larger thing they are working on. They get very good at one of the tasks, but lose touch with the larger picture. So we have to design rigid policies and procedures so people will function efficiently and so they won’t interfere with each others’ work.

The problem comes with scale. As the number of employees grows, the profit per employee shrinks. It’s a game of diminishing returns. Efficiencies of scale are balanced out by the burdens of bureaucracy. Divisions become silos, disconnected from each other. Overhead costs increase with size. The resulting need for control, and the inability to achieve it at a reasonable cost, is what eventually kills a business.

DESIGN BY CONNECTION

Although we tend to design companies like machines, we instinctively and intuitively understand that companies are not made of cogs, levers and gears. In the end, they are made out of people. For top management, it would be wonderful if we could put our business strategy into the machine, push a button and wait for the results. But it doesn’t work that way. You have to put your strategy into people if you want to get results.

And today, thanks to social technologies, we finally have the tools to manage companies like the complex organisms they are. Social Business Design is design for companies that are made out of people. It’s design for complexity, for productivity, and for longevity. It’s not design by division but design by connection.

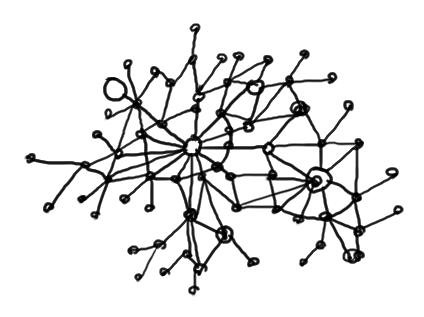

To design the connected company we must focus on the company as a complex ecosystem, a set of connections and potential connections, a decentralized organism that has eyes and ears everywhere that people touch the company, whether they are employees, partners, customers or suppliers.

Social Business Design is a new discipline, but some basic rules are already emerging. These emerging rules have less in common with traditional business design, and more in common with urban design and city planning. It’s not about design for control so much as design for emergence. You can’t control a complex system, but you can manage its growth, and there are a lot of things you can do that will position it for success. Here are a few of those emerging practices that signal excellence in design by connection:

Understand the culture: A company is like a city in many ways. First and foremost, a city is about the people who live and work there; it’s an expression of their collective culture. Before you can start your path to the connected company, you need to understand the culture (or cultures) that are already there, so you can look for ways to enhance and strengthen that shared identity.

Start small. Urban designers might look at maps or aerial views as they make their plans, but the life of a city happens at street level. As you initiate social programs, think of them as if you are designing a city street. A successful street is filled with people. The last thing you want is a whole bunch of large, urban areas with no people in them. In a city, big, open, empty spaces feel unsafe and unloved. So start small. The smaller the space is initially, the faster it will fill up with people. A good way to start is with an organization-wide project or initiative that requires participation from a number of people across the company. This gives you a cross-section of ideas and perspectives to look at as you plan the next stage.

Spaces need owners. Again, think of the city street: every business or building has an owner. The sidewalks have owners – typically every business at street level “polices” their stretch of sidewalk. And even the street has owners – the street sweeper, the cop on the beat. In the same way, make sure that every online space you create has someone positioned to take care of it, to keep it safe and clean.

Every person needs a place. In the same way that public spaces need caretakers, every person needs a place to live; somewhere they can put their stuff. As you build your social business, make sure that every single person has a place where they can put, and see, their stuff: their projects, the links they want to get back to, the documents they have created, their role, qualifications, expertise and so on.

Jumping-off points. A good city street offers opportunities that are unanticipated but serendipitous. The promising side-street. The sound of music coming through an open door. As you design for connection, think about how you might create those unexpected, but delightful, surprises. Every time someone visits an online space, there’s a chance to offer them something new.

Watch, listen, adjust and adapt. Design by connection is not a top-down activity so much as bottom-up. Complex systems just don’t work that way. In a complex system, you need to pay attention to small things and make little adjustments along the way. Think about how city streets evolve: one small step at a time. One retailer moves to a larger space; another goes out of business. One old building is torn down and replaced; another is rehabbed and turned into lofts. Pay attention to the culture, and watch how people react to the tools you provide. Are they using something in a different way than you expected? Find out why and see if you can enhance that. And what are they ignoring? If they’re not using something you expected them to use, go talk to them and see if you can figure out the reason.

The typical company has a very short life, from 15 to 50 years. But cities – and some companies – live much longer lifespans: from hundreds to thousands of years. Wouldn’t you like that for your company? I know I would.

If you have thoughts I would love to hear them. Please take a moment and leave a comment.

UPDATE: The book "The Connected Company" is now available on Amazon!

UPDATE: Based on the extreme volume of response to this post I have set up an email discussion group for those who want to continue the conversation. Please join us here.

Keep in touch! Sign up to get updates and occasional emails from me.

59 comments:

Absolutely love the post Dave. My comment has little to do with it, and rather a question instigated by it. You asked me to post here, but this will be a little stream of consciousness so bear with me.

It brings to my mind the question of what kinds of exceptions exist to some of these planning rules?

Specifically, when is inefficiency ok, or at least acceptable? On the machine/technology front for example, I think you could argue that the military drive a lot of innovation that would never be possible in a truly efficient business system. (It is only the excess resources that allow for experimentation for purposes other than a financial return...those then trickle into the commercial sector later where they are monetized). That would be the case whether aligned along 'organism' or 'machine' business shaping models no?

On an innovation front, when is an excess of resources a requirement for focused innovation, and when does a limitation of those same resources foster it. Think US vs. Russia space program..both with massive innovations to achieve the same purpose but with very different priorities and resources. More importantly, is there a way to identify those times when a surplus or a dearth of resources is most appropriate to achieving innovation goals? I used to struggle with some of this in companies where I was working on innovation culture development and I'm wondering if you see an impact that an organism model could make on that.

Sorry for the free flowing thought.

Cheers,

Matt Ridings - @techguerilla

Very insightful post; this is the type of macro-level thinking that creates a "corporate culture" (I hate even using that phrase) worth working in. My Father, and I are entrepreneurs and have theorized similarly. This also reminds me of Metcalfe's law, and the idea of a networked system having more leverage. Good stuff.

Great comment Matt. Funny you should mention the idea of resources applied to innovation. There was one finding of the Shell study that I didn't mention, and that was that long-lived companies tend to be financially conservative. They don't take on a lot of debt and they maintain healthy reserves of cash.

This gives them the flexibility to aggressively pursue opportunities whenever they see, or "sense" them in the marketplace.

This is important because when you have a truly unique or promising opportunity -- say like Apple did with the iPod/iTunes ecosystem -- you don't have time to go around selling the idea to banks and investors, who are traditionally very dumb and driven by their conceptions of what worked in the past.

When you're designing the future you need vision and foresight, not hindsight. And to make things happen you also need cash.

The long-lived companies save their cash for a rainy day so they can jump on promising opportunities when they arise.

Hope this helps answer your questions. Loom forward to heating more of your thoughts!

Good Lord, Dave, we're going to have a lot to talk about when you're visting here next week. Not what is in your brilliant post. We see the same reality. Our thinking is interchangeable. What will be fun is dreamstorming what we can build atop these ideas to make the world work better. I have a never-ending supply of flipcharts, markers, and post-its waiting for you here in the Internet Time Lab in Berkeley.

Great post, by the way. I usually take twice that many words.

See you soon.

jay

Still digesting this, Dave, just wondered if you'd read Gareth Morgan's seminal 'Images of Organization'?

This is truely fascinating stuff and the analogy seems helpful enough to understand the inner workings of a company behemoth and how to structure it in a beneficial way.

On an off-topic tangent I am wondering however, if building more self-sustainable, rejuvenating companies is necessarily something a society should strive for. Because at the end of the day a company is much different from a city in that its vested interest are those of its shareholders, aka the bottom line. A city is an organism by and for its inhabitants, there are no stakeholders with ulterior motives.

So the direction in which a company evolves is driven by different constraints than those that are beneficial to society. The question I have in this respect is: Can their respective interests be aligned?

Fascinating post, thank you.

You hit the nail on the head when you say, "You have to put your strategy into people if you want to get results." I do wonder though whether your continuation, "To design the connected company..." begs the question.

As John Hagel et al will argue, we're seeing a big shift from the institution to the individual. If we're applying systems thinking to productivity, should we automatically presume that the limited company or corporation is still a relevant vehicle?

Perhaps we have to innovate past the company for people to reach their full potential.

Fascinating post and full of good stuff. But isn't it based on a false premise?

Because the average life of an S&P 500 company is 15 years it does not follow automatically that these companies are "collapsing under their own weight". Some merge, some are acquired, some exist for a specific purpose and have a natural life span.

There has been an apparent fall in average company life expectancy from 75 to 15 years. So what? Do we seriously believe the world would be a better place (however you measure that) if more of those big companies from 1937 were still around now? In fact, I think I prefer a world where new companies with new ideas are regularly springing up and replacing others. Maybe 15 years is too long not too short an average life span.

Excellent post. At points my mind was singing along with your flow, at other times grinding the gears trying to understand. But lots to think about. I am particularly interested in how these theories play out in the social sector--philanthropy, international aid, and nonprofit organizations--which is where I live. We have, to our detriment, applied machine thinking to social change as well. It is how we apply 'discipline' to what is definitially messy work. Rather than link and iterate, we want to decide and direct. My post "Farmers or Merchants" (http://wp.me/pH1Mf-2k) is an allegory that floats somewhere near these good ideas of yours. Looking forward to learning more from your work.

I'll admit my first reaction was that I don't necessarily think that the shortening of company "lifespans" is a bad thing.

Very interesting post. Very much in line with Gary Hamel's book 'The Future of Management' where he expounds on decentralized management and how companies will be run in the future. You should check that out. It's also related to what I read recently in Steve Johnson's 'Where Good Ideas Come From' which is no surprise that customers who buy the 'Emergence' book also buy the Johnson book on Amazon.com.

I'm posting as an interested but almost totally ignorant newcomer to the world of, well, business. This was fascinating, and carries on a theme I've been seeing in the posts all over twitter, which is about putting the spirituality and humanity back into a business context... I'm very heartened by this and hope this attitude continues and grows.

Part of the reason why cities grow more efficiently comes from the free-market nature of their growth, not so much from its connectedness. In fact I consider the connectedness a side-effect of the free exchanges amongst citizens and local businesses.

I have theorized along these lines in an two-part article (see links below).

In short, I believe companies should enable employees to self-organize along business objectives mined by its customer-facing people, aligning their incentives and recognition with peoples ability to recruit and be recruited in its internal market. The alignment of recognition with an internal free-market must be backed by an internal information market that allows people to exchange information about their own work so that ensuing mutual trust facilitates quick transitions across projects.

Well, that is the 2 minute summary, the whole theory is outlined in:

The Commanding Heights of the Enterprise – Part 1 – The free-market workforce

The Commanding Heights of the Enterprise – Part 2 – The information market

Really like the post. It is an interesting coincidence that recently I read Paolo Soleri's The Omega Seed. This was the philosophical under pinning of the theory of Arcology.

Arcology is a portmonteau word that combines architecture and ecology. The original intent of the arcology movement was to address the ecological impact and influence on the development of large urban centres. Here are some of the principles he used to design his cities:

- maximize human interaction

- shared, cost-effective infrastructure services

- reduce waste - conserve consumption

- maximize the use of resources

- allow interaction across the environment

Interesting, no?

The author William Gibson coined the phrase 'corporate arcology' referring to the underlying structures, culture and automation that drove the corporations' power base.

Your reference to cities as a source of inspiration rang a familiar tome with me. I have been pondering the potential for launching a corporate arcology movement to replace enterprise architecture.

Mike Lachapelle

@davegray via @sachac In your company as machine, as organization, design by connection, you might be interested in foundations from Ackoff & Gharajedaghi 1996, "Reflections on systems and their models". I've reproduced the table in a map at http://coevolving.com/aalto/201010-cs0004/201010-cs0004-map01-foundations.html , as part of class at http://coevolving.com/aalto/201010-cs0004/201010-cs0004-map00-context.html .

Dave -- that is a very nicely condensed account on Systems Thinking applied to Organizational Design & mirrors what I have learned so far -- I am not so sure about the term 'Social Business Design', but that will be an excellent startingpoint for an conversation when we meet in SF next week -- looking forward to it! Alex

This post is brilliant and important, Dave. I want you to turn it into a book for me :-) Let's talk about that.

The insights here have the beauty of obviousness in retrospect, even though it's clear that no one has connected the dots in quite the way that you do.

I'd love to see stories told about companies that do organize this way. I know lots of stories about companies that excel at individual pieces of what you talk about here, but it would be interesting to explore each in more detail.

hi, big parts of this theory are written down in the book of gareth morgan: picture of the organisation, in germany published around 1996. finally we start to listen:-)

dagmar

shifting from metaphor of machine to metaphor of organism is most useful if it leads to explanations of how it works, and therefore exposes levers for intervention. discussion of structures doesn't necessarily lead to causal understanding [and if there are no causalities, we can only act randomly and hope].

so, i prefer the alternative model [not just metaphor] of organizations as conversations. because coherent actions coordinated in the market are the only mean of organizational success [by any criteria], and because agreement must precede coordinated action, and because conversation must precede agreement, in principle this seems like a fertile direction. in practice, it forefronts all the possible levers, and can also incorporate that pesky but always-present social component of organizations: we are all human beings acting in our own self-interest.

from these realities, design of organizations can be a methodology, more than a process.

Peter Philips made the same observation that I was going to make: I want to know more about the context for determining the lifespan of those S&P 500 organizations? Were they merged/acquired out of existence or did the organizations.

That of course is a relatively minor point however in the context of the larger idea here re: how we conceive of and structure large organizations successfully. The city analogy is nothing short of extraordinary and the reasoning all works.

What a powerful way to re-imagine the importance of corporate culture!

The idea of a company as as city/organism makes intuitive sense, but also raises a lot of questions, as these comments indicate. My first one concerns the concept of "mission." Most management gurus would say a company should define its mission and organize itself to accomplish that mission--which suggests it is,in your terms, "a machine designed to perform a certain function". Cities, on the other hand, don't have mission statements; they have cultures. They may be more productive, but what they produce is more diffuse. If we start thinking of our company as a city, do we have to move away from carrying out a mission?

The commenters who ask whether it's a bad thing for a company only to last for 15 years may implicitly be raising this question. If a company has fulfilled its mission in that time, maybe its demise is appropriate?

Thanks for this fascinating and provocative post.

This is a fascinating post and echoes (although in far better explained and illustrated ways) my own thinking about organisational design and how we work within what Shirky calls 'frozen accidents'. I lecture in media in a small UK university centre where we have so many brilliant, energetic and believing people separated by the walls (some physical, some notional such as faculties, job descriptions and grades) which deliniate the 'cogs in the machine'.

I finish my Masters this week (all being well with distinction) and I presented a sort of 'positioning statement' to colleagues entitled "Out of the plant-pot and into the Garden: Toward a knowledge ecology". You can find it here if you want to watch or read it.

I don't really have anything to add to the great conversation which is going on here, but I am considering PhD study in the area discussed and wonder if any of you have thoughts about what might be a useful and valid research thesis/question or where else I should be looking?

I loved the concept of "Design by Connections". This is something all the companies should do.

I want to ask for permission to translate this article to Portuguese and post in my blog, with references, of course. This is something all people should read and think about.

Dave- great post! Looking forward to more!

I think the rapid reduction in average lifespan is not a bad thing. I'm sure that the rise of VCs and Angles and the entrepreneurial boom over the past 20 years have helped escalate the trend.

There are many long-standing companies but there also many more (exponentially more) startup and small companies that don't make it past year 5 because investors, not the creative entrepreneur, decided it was time to fold the cards.

As I work in innovation research, I see great ideas from both big and small (startup) firms. Big firms must keep the innovation pipeline filled, but entrepreneurs have the ability to move to the next thing becoming a "serial entrepreneur," so that their ability to add to the overall volume of companies is greater.

Randy @IpsosVantis @randygiusto

Some great and challenging thoughts here, Dave.

I think that the most important one from my point of view is the analogy of companies to cities.

For a way of peeking into the complexity and dynamics of the entity we call a city, check out Richard Saul Wurman’s project 19.2..21 http://www.192021.org/ and imagine the way we might make such “maps” of companies.

To me, the power of the analogy to cities lies in the complexity of moving parts, from public works to the ethos of the life in a city’s parks. The diverse sources of activity and material that together constitute the city are neither completely planned nor completely unplanned. Consider New York’s Central Park, which from the beginning was made on a plan that by definition had the unplannable element of the organic at the heart of its design.

One of the things missing from your perspective here, Dave, is the most important idea from Steven Johnson’s most recent book, Where Good Ideas Come From. Johnson calls attention to the crucial (and often unconsidered) fact that complex phenomena play out on multiple scales. This is the “dimensional” aspect of complexity, which leads to multi-layer, and multi-speed causality.

Clearly there are elements in companies, as in cities, that can and should be managed and other that must be designed for and with. In either case, the activities of managing and designing must be constant and engaged and at more than one scale.

I think that something else implied by your analogy is that cities that survive and thrive are perpetually unfinished. This to me is the most interesting and important point of your contrast between company as machine vs. company as organism. This relates to the difference in the sense we give to the idea of purpose when we think of a machine. One a machine is built, the die is often cast with respect to its value and uses. An unfinished design, like a city (a company), unfolds over time.

The question for me about both cities and companies, as I suspect it is for you, is how we can increasingly open them up as platforms for design that there citizens/”users” can extend. This has always happened in both companies and cities, but we have interesting new design tools that allow us to play at scales we never could have imagined before.

My last thought is that we should be careful of the either/or hypothesis. We don’t need, in order to take seriously your idea of “design by connection”, to think of companies as being EITHER machines OR organisms. They are both, and in each case, there is more than one kind of each. Cities are grids of electricity, circulatory systems of water and machines of governance from courts to trash collection. They are also made of humans, plants and animals, as well as many other forms of organism at various scales, including the city itself. It is designing for BOTH the machines and the organisms that makes design for emergent systems so challenging and interesting.

I’m grateful and hopeful that you and companies like Dachis are trying to help others struggle with and design for these challenges even while you struggle with them yourselves.

The slower a tree grows, the longer it lives. The faster a tree grows, the sooner it dies.

I quoted this post in a speech today and have several requests to copy listeners. Thank you for providing such insightful information in an interesting way.

Jeremy Broussard

Thank you for all the great comments and reading suggestions. There's so much richness here I think it would be better to respond in another blog post (or maybe several).

Douglas -- yes, please feel free to translate to Portuguese and please link back to the original post.

Doug and Dagmar -- I was not familiar with the book "Images of the Organization" but I am excited to read it and look forward to sharing more ideas when I have a chance to digest it.

I'm going to spend a bit of time digesting all the feedback, clarifying further thoughts and following up on the reading suggestions. You can be sure I will have more to say on the subject.

Meanwhile if any of you can share examples of things you have seen or experienced that "confirm or deny" the assertions I made in the post, please don't hesitate to share them.

I look forward to continuing this conversation!

Dave, so many topics to talk about and so few characters...

Excellent post. Really enjoyed it.

Somethings to think about:

How do you propose decision making is occurs in an connected organization? I am no management guru, but have experienced different style organizations with committee decision making (nothing ever gets done) to top down models (stuff gets done, but with resentment and inefficiency.)

Personally, at Conversify, I take the role of a benign dictator overseeing entrepreneurial types. I encourage creativity and problem solving amongst my troops. I empower them to get things done, but want to be there to provide advice. I'm aware of the greater impact of what happens on both the left and the right and I encourage connection as well as understanding the other's viewpoint. This works because, while, we're multinational, we're still small. How does that work for a larger company?

Second, how do you deal with the concepts of Roles & Responsibilities? Something I have been pondering lately. I'm a big fan of the concept that not everyone you hire to do a job will be the right person for it. So how do we change the internal process, mentor the person, change the role, define their strengths, etc. so as to set everyone up for success. Again, this is fine in a small entrepreneurial organization where roles & responsibilities are in flux, but in a larger one where when you need to know who to call to get X done, having loosely defined roles can curtail efficiency. [Just read "Now Discover your Strengths" and am trying to figure out how this all fits in.

Lastly, and this is directed at Peter, I can't come up with an example of a city government coming up with a mission, but when Kennedy said we would put a Man on the Moon, he gave the country a Mission. I think that kind of inspiration can come from a great leader or from a group of people in the trenches that bubbles up and then is adapted by a leader.

Keep it coming..

Monique @MoniqueElwell

I'm posting a comment here that I received by email from Christian Smith-Socaris, with his permission (Thanks Christian!):

A few quick comments that might be clarifying:

"the average life expectancy of a company in the S&P 500 has dropped precipitously, from 75 years (in 1937) to 15 years in a more recent study. Why is the life expectancy of a company so low? And why is it dropping?

I believe that many of these companies are collapsing under their own weight. As companies grow they invariably increase in complexity, and as things get more complex they become more difficult to control."

Companies clearly do not "invariably increase in complexity" as they grow. Complexity is the result of non-linear interactions, two individuals can have a complex interaction and a billion could have a non-complex one. Most traditional industrial orgs don't increase in complexity much as they scale and that is the problem (the one that he goes on to suggest solutions for that would in fact increase the complexity of the org; it isn't about managing complexity it is about creating complexity and harnessing that which is arising spontaneously, essential difference!)

To talk about the life expectancy of a company is to consider it as something that exists in cycles of generation. When talking about organizations a much closer analogy is speciation and extinction. If the question is "why has the extinction rate for businesses increased?" we would naturally be led to the question "what has been going on with the speciation rate?" which begins to suggest the appropriate frame: ecology. One company changing its practices won't change the extinction rate, because these are macro-properties of the whole community of organizations.

"To design the connected company we must focus on the company as a complex ecosystem, a set of connections and potential connections, a decentralized organism that has eyes and ears everywhere that people touch the company, whether they are employees, partners, customers or suppliers."

Again, the company is not a complex ecosystem, it is an entity of relatively low complexity (though increasing) in a complex ecosystem.

The crux of what he's really talking about is adaptability (fellows will remember this from the talk I gave). Systems in general exhibit a range of behavior from completely deterministic to completely unpredictable. Complex, adaptive systems exist in the area of the phase transition between these two regimes. Dave is first hypothesizing that current org structures and processes are less adaptive then is possible, and second, that increasing the connectivity of members of the organization while simultaneously increasing their autonomy will push the org toward the stochastic regime and increase its adaptability.

The long lived companies are: decentralized entities with strongly aligned employees that are well attuned to their environment. Sounds like a herd, which it is in many ways. It doesn't sound like an ecosystem, and only partially like an organism. It is really about how do we create a cohesive and highly adaptive sub-population, that exists in a ecosystem that is increasing in complexity due to rapid and distributed network formation.

In sum, Dave I think ends up with some good proscriptions from an organizational strategy perspective, but he really seems to misunderstand the basic dynamics he is describing.

Christian

Dave, I've been working on a digital infrastructure that would follow the "city" model for a while now. So I was very interested in your post. Our current architecture of "web sites" and "personal computers" doesn't really lend itself to a "city" like organization.

Saw that JSB talk at CCA. Really gets your blood pumping doesn't it?!

Great post.

Love the back hoe sketch.

Superb post, thank you. It's a terrible shame that the Shell study was never published, I think the wisdom contained in it might help a lot of people at this point in the game!

A very nice summary, Dave. It's good to see something that puts a systems thinking spin on social networking (or a social networking spin on systems thinking!).

Some random comments:

1. You mention the decline in the average life expectancy of a company in the S&P 500. I assume that's a mean average. It would be interesting to know the median and modal averages, too.

2. On Arie de Geus's study. The first two characteristics -- ecosystems and strong identity -- are probably linked. It's likely that only those organisations that have a strong culture, sense of mission, "message to the world" or whatever you call it dare to give such freedom to the periphery.

At the time I first read the book, I was working for Harold Geneen's ITT, which seemed to stand for nothing except making money and kept every employee, division and subsidiary on a very tight leash. The thought police were accordingly vigilant.

3. On cities and their growth, Jane Jacobs and Lewis Mumford had much of value to say on the destructive effects of simplistic urban planning and are worth reading even today.

4. On systems thinking in general, Daniel Aronson has a page of links here -- http://www.thinking.net/Systems_Thinking/systems_thinking.html -- that might be helpful to those new to the topic.

5. Re Images of Organization. There's a 1996 interview with Gareth Morgan here -- http://www.imaginiz.com/provocative/metaphors/questions.html -- that's worth a read. The analysis section of his book is brilliant, IMHO, but I remember being less convinced by his proposed solutions.

Keep up the good work!

Regards,

Roger Whitehead

I've proposed (arguably) more comprehensive solutions to decentralizing companies and governments. I like your setup of the issues and high level goals.

The first key to promoting more egalitarian decentralized organizations is to make them financially egalitarian. This article details the financial system for how partners can buy-in, sell-out or even secede/abandon completely the partnership.

http://www.naturalfinance.net/2011/01/communal-equity-accounting-re.html

The other key to decentralization is recognizing that while functional areas need supervision does not imply the need for a hierarchical pyramid of supervision headed by a single individual. What I call natural governance focuses on setting up functional responsibility silos chaotically through partnership democratic approval, along with elected partner delegates supervising/regulating the function.

http://www.naturalfinance.net/2011/01/natural-governance.html

Excellent post and completely agree. Companies have to move beyond simplified mechanistic thinking and accept and embrace the complexity and chaos of the real world. Business needs to stop clinging to the comfort of the over simplified symbols of reality and accept the complexity that really exists.

Yes, yes, yes. And if you are going to turn it into a book, I volunteer to contribute some thoughts, as I find quite many connections in your post to my proposal on what a company is. Based on systems theory (Luhmann) I started reading the studies of US researcher Harrison White, of whom I recommend to read "Markets from Networks" and "Identity and Control". A fundamental thought I found there, is, that networks (or the connected company) are not only the future of organisations but their very origin! If you read the statistical studies you referred to with that in mind, I bet you'll find that the immortal corporations where able to maintain and rejuvenate their networks - just like cities.

However, as has been stated above, a company by its very nature is a reduction of complexity. So how does that fit? I propose to think of companies as entities carved out of the network/ecosystem, which is essentially us, the world. Now the question is, how do you carve out such an entity? My proposal: by communication or more precisely by discoursive practices. In that model a corporation - as well as a non-profit, or a political party, or an university - is composed of its discourses and it exists as long as its discourses exist, or less scientifical: as long people speak about the company. As proof of concept I propose to apply that thinking to truely almost immortal entities: brands. Strong brands do not die, even if the companies that produce them cease to exist. Even a brand as Enron, surely no love brand still marks a relevant position in certain discourses. It serves as an address to which you can attach all things you do not want to see in a company. A discoursive model of the company also helps to understand how it is possible to manage a decentralized, heterarchical entity, not by command and control but by discourse. As long as you offer a valid strategic narrative the stakeholder of the company will relate to it and keep the company alive. And even if the company fails to deliver, its members might loose the job a company A, but if they are good at what they do, you can be sure that they will be able to use their skills within another company. Finally, a probable explanation for more and more short lived companies might be owed to the dynamics (speed) and diversity of modern societies. It might not be the weight, under which they collapsed but the inability to establish a management model that enables and encourages their employees to adapt to quickly changing discourses whereas the immortals either are an essential part of "old" discourses or found a way to enhance their connectedness - thing GE or Apple.

Great article. Got me thinking about thinking about going back to reading the two Gareth Morgan books that have been gathering dust for 10 years!

Great synthesis of ideas in a very accessible and compelling presentation. I hope you'll take Tim up on his offer to grow this into a book. Seems like you could follow your own prescription about starting small and providing jumping off points ... and it's clear you're already watching, listening and adapting.

I see many elements here that reflect some of the insights of William Whyte, and his classic work on the Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. I have no doubt you are well aware of that work, but given your reference to social technologies, I wanted to recommend more recent, related research that may not yet be quite as famous: Keith Hampton, Oren Livio and Lauren Session's study of The Social Life of Wireless Urban Spaces: Internet Use, Social Networks, and the Public Realm (Journal of Communication 60(4), 701-722. 2010). An associated photo essay, and other potentially relevant studies, can be found on Keith Hampton's publication page.

I've enjoyed the post and the discussion thus far very much!

Social Business

For social businesses, the value is in the connections, and it is the untapped value that is recognized by identifying gaps and opportunities between groups/divisions/products/offerings/partners/clients... and having a network that is aware enough to do something about it.

A very recent example of this was my becoming aware of a business opportunity surfacing in my network that I thought might be interesting to another portion of my network, and making them aware. in the past, this might have involved clipping an article out of a newspaper and mailing it (doesn’t that seem quaint now?) -- now, it’s an electronic notification, and in the (near) future it could be the self-aware machine learning network that surfaces these opportunities, prioritizes them, and shares them during an appropriate context sensitive time.

from one of my posts in the Social Business Jam:

“the great value that is created in a social business is by discontiguous / disparate nodes (people or processes where there is a gap that is understood by those affected. in a world where c naturally follows b, which of course follows a, there's limited value to exploit between a and b. in contrast, there could be huge value in linking a with 6.02x10^23 because the network understands there's a connection, and the social business-enabled system can adapt to provide that connection.

where standardization and automation have done much to accelerate the creation of mass produced things, mass personalization can be reached as individuals, teams and companies dynamically identify value and work to realize it. incremental improvement of structured processes, while still having its place, will not yield the step-change benefits that those that employ social businesses practices will reap.“

Social Business Jam

Architecture of Social

Like many others, the following concepts deeply resonated with me --

“design for emergence”, for managing growth, etc.

“design for connection” -- this is precisely what microblogging and social bookmarking can allow... the serendipitous connection between people who by happenstance sense and see what’s happening in each other’s activity stream. I can forsee a time when systems, especially when you see how the machine learning exhibited by the Watson computer that will compete on Jeopardy! this week, will be smart enough to alert individuals in a context sensitive way to information that is relevant to what they are doing, while they are doing it. The links, for example, that I’ve peppered through this response would be made available to me via a Tweetdeck or similar such approach, just as I needed them.

Nova’s Will Watson Win Jeopardy

I liked what Mike Lachapelle had to say about Paolo Soleri’s The Omega Seed, and Arcology. When thinking about designing human spaces, Tom Peters concept of “the little BIG things” -- the quality of a spectacularly clean bathroom, springs to mind, precisely because it helps to create a place where people want to be, and feel valued to be there.

the little BIG things

Project for Public Spaces, after analyzing what makes a public space successful, concluded that there are four key qualities, the place is accessible, comfortable, sociable and people engage in activities there. The Place Diagram developed by the Project for Public Spaces helps one judge a place.

Project for Public Spaces

Dave’s post has got me thinking about refactoring/designing a “place diagram” that is representative of how to identify a great company -- one that has a fighting chance of enduring well beyond the average.

This sounds a lot like "Power to the Edge" (free book at www.dodccrp.org/files/Alberts_Power.pdf)

Interesting post but I believe you are comparing apples to oranges in your analysis. Yes, cities seem to endure but neighborhoods in the cities have a much shorter lifespan than the city they are in. Paris has been around since 52 B.C. but you can bet that the neighborhoods have changed greatly in the last two millennium.

A more appropriate comparison is between cities and industries/professions. The profession of law has been around much longer than any law firms that exist in the profession. The same can be said for engineering and the firms that make up engineering. You may want to examine what makes a profession endure to determine the role of communication and connectivity.

I also tried Googling the exact number of cities in the world. There was no definite answer but I can safely assume that there are at least over 100,000 distinct cities in the total history of humanity. Thus, when you compute the average lifespan of a city you may find it averaging much less than the large numbers you quote. Even so, I believe that you will find a rough parity between the longevity of cities and the longevity of industries/professions.

Again, you have some interesting points but I think that Eric Beinhocker has covered similar concepts in his masterful Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics.

Brillant!

Very engaging story, but ...

Did you happen to read the Update section at the base of the Cybaea journal's finding? It links to a second article titled 3/2 rule revisited.

The key point from that one is that it isn't as hugely drastic as 3/2 as it said after they looked at a larger sample and separated the industries. There still is a drop by size, but the "scary" part is much more muted if not nullified.

When looking across all industries and companies, rather than "if you grow by 3x, it will drop productivity by 1/2", it is more of a 10% drop vs. 52%. If you grow by 10x, their calculation would result in a 20% drop. By a 100x it would be a 37% drop. That is enormous growth by any standard.

Those numbers are still disturbing and they still support the declining scale issue.

However, it starts to look much better if you don't lump all companies across all industries into the same pile. When you look at the per industry charts it is much smaller, flat or even growing in industries like healthcare, technology, services and industrial goods. Financial sector and Conglomerates were the worst offenders. The Financial sector is the only one with sufficient data that bears out the problem of 3x employee size growth might lead to ~50% drop.

In healthcare sector, growing by 3x leads to 3% increase in productivity. Not much of a gain at all, but it isn't dropping. In technology companies, growing by 3x leads to a 2.6% drop in productivity.

If you ask most companies, they'd be willing to risk the increase in overall revenue, profit and market impact at the risk of so little of a loss in productivity.

Hey, I'm just going by their data and calculations.

For those who want to continue the conversation I have set up an email discussion group here.

I hope you will join us there!

Rawn, there's a more recent study by the same group here which seems to confirm the initial findings.

Still, the point is that as companies grow their productivity tends to decrease. The idea that the rule doesn't apply to health care doesn't surprise me, since health care costs (at least in the US) are highly inflated. I expect you might find a similar "productivity" law in higher education.

To be clear, I'm not trying to say that companies can gain productivity as they grow. And I'm not saying that every company needs to undergo radical change. I just think that we can do better.

I think this is great Dave! I think it is VERY timely too as companies have moved away from producing physical goods and now produce digital information. This changes everything and I think your ideas can be very fruitfull in regards to large companies changing. I think it is obvious that it is harder to change a car factory to a helicopter factory that to change from selling music CDs to movie DVDs. Also, I think it would be great to have leaders running the companies NOT trying to control everything which ultimately are impossible to control. Its a very different way of looking at things. In the science field there are things called emergent systems.

Accidentally deleted this comment this morning. Pasted and copied from my email here. Sorry Pawan!

Aparna has left a new comment on your post "The connected company":

Wow Dave, what a luminous post is this....actually its very true and also that people like you have to come ahead and look for the health of the companies. We have to bemore worried fore the health n life of a company equally as we are worried for the bottom line. I'm sure many more similar posts will come from you. At least this post of yours will force many professionals like me to contribute in our own little way to be thoughful for the life span of our companies and while doing so, various input would be required from people like you.

Brilliant stuff, Congrats!!

Pawan

What are you classing as a company?

Because I've had online businesses that only last a couple of months. I wouldn't class that as a company but if things like that ares put into the statistics, it will drive the figures down.

Spiral Dynamics explains this phenomenon from a tribe behavior perspective. All groups, not just companies, are moving towards more organism-like systems. The top-down system was necessary and useful at a certain stage of survival, and now we're out-growing it.

Great post, very nice insight.

Hi, Dave:

Everytime I drop in into your blog I have a good time at gathering "food for thought". Your article "The connected company" is excellent.

In my opinion, the city example may well be the right one for existing large companies, but for start-ups, my domain as you know, I prefer the organism type of comparison.

We miss you in Madrid.

Rodolfo

Dave,

"The connected company" was an excellent post and very thought provoking article. I'm currently Training & Development grad student and I've studied a bit on organizational development. I think that all training professionals should have a working knowledge of how companies really have functioned as machines historically and how we as professionals can contribute to the growth and evolution of this type of structure and extend the life expectancy and improve the internal functionality at the same time.

Very good food for thought, thanks for sharing the post.

Sabrina Warner

Dave,

"The connected company" was an excellent post and very thought provoking article. I'm currently Training & Development grad student and I've studied a bit on organizational development. I think that all training professionals should have a working knowledge of how companies really have functioned as machines historically and how we as professionals can contribute to the growth and evolution of this type of structure and extend the life expectancy and improve the internal functionality at the same time.

Very good food for thought, thanks for sharing the post.

Sabrina Warner

organizations as living systems = http://www.dubberly.com/articles/notes-on-the-role-of-leadership-and-language.html

Dave, "The Connected Company" was one of the more insightful articles on how to structure a successful company.

Correct me if I'm wrong, but I just kept drawing comparisons between your concept of a company as a city and the concept of the Lean business. Both have to be organic, innovative, and most importantly adaptive. Control and decisions must be distributed in order to maintain agility.

My question is this: rather than focusing on the larger companies such as Shell, what advice and structural suggestions do you have for the smaller companies that are still trying to define their presence in the market place and do not yet have an identificable culture? What steps can we small business owners put in place now in order to account for the dilemmas you mention prior to growth?

Once again, such valuable information and thanks so much for sharing.

Cheers,

Greg - @gregsuch

Hi Greg,

That's a great question and deserves a longer answer than I have time to give you today.

Just like a city, any organization, large or small, must find a way to balance individual freedom and the common good.

The greater the individual freedom, the greater the potential to adapt. Focusing on the common good requires that you put some constraints on individual autonomy. The "degree of constraint" will both focus the organization and limit its ability to adapt.

It's a balancing act between being flexible enough to learn and consistent/efficient enough to move toward shared goals.

Most of the time we err on the side of efficiency, so I would say that one thing you can do is, every time you are discussing a move to increase efficiency, you might want to ask, "what flexibility and adaptiveness are we losing as we make this step?"

@Greg

I think another question might be how to create the kind of culture within a smaller organization that cultivates the kind of flexibility and adaptability that is required to innovate and grow. Even small companies that have only been around a short time, already have the seeds of culture - it is prudent to design that culture in an intentional way so that core values and vision are essential elements of every decision. Too often small businesses fail to think strategically aout the culture they are creating, especially if the founder has trouble letting go of control and delegating to others. Companies have to value connectivity and organic growth over protecting company secrets and avoiding failure by playing it safe. Interesting discussion. Thanks for your comments.

I agree. Companies have become increasingly complex and this has lead to a lot of companies' downfall. I think another reason why the life expectancy for a company has decreased so much in recent years is because new companies take on too much overhead too quickly. You don't have to rent out 3,000 sq ft of office space to get going. Work out of a home office first. You don't need all the latest and greatest technology. Just get going with a basic PC or laptop.

In short: You can be in control without controlling.

Exactly :)

Post a Comment